Visits: 14

– The design could advance the development of small portable AI devices.

Courtesy MIT by Jennifer Chu: MIT engineers designed a “brain on a chip”, smaller than a piece of confetti, made of tens of thousands of artificial brain synapses known as memristors – silicon-based components that mimic transmission synapses of information in the human brain.

The researchers borrowed the principles of metallurgy to manufacture each memristor from silver and copper alloys, together with silicon. When they ran the chip in various visual tasks, the chip was able to “remember” the stored images and reproduce them over and over again, in clearer and cleaner versions compared to the existing designs of memristors made with unbound elements.

Their results, published today in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, demonstrate a promising new memristor design for neuromorphic – electronic devices based on a new type of circuit that processes information in a way that mimics the neural architecture of the brain. Such brain-inspired circuits could be built on small, portable devices and perform complex computational tasks that only today’s supercomputers can handle.

“Until now, networks of artificial synapses exist as software. We are trying to build real neural network hardware for portable artificial intelligence systems, ”says Jeehwan Kim, associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT. “Imagine connecting a neuromorphic device to a camera in your car and having it recognize lights and objects and make a decision immediately, without having to connect to the Internet. We hope to use energy-efficient memristors to perform these tasks on the spot, in real time. “

Wandering ions

Memristors, or memory transistors, are an essential element in neuromorphic computing. In a neuromorphic device, a memristor would serve as a transistor in a circuit, although its functioning was more like a brain synapse – the junction between two neurons. The synapse receives signals from a neuron, in the form of ions, and sends a corresponding signal to the next neuron.

A transistor in a conventional circuit transmits information alternating between one of the two unique values, 0 and 1, and it does so only when the signal it receives, in the form of an electric current, has a particular force. On the other hand, a memristor would function along a gradient, like a synapse in the brain. The signal it produces varies according to the strength of the signal it receives. This would allow a single memristor to have many values and, therefore, perform a much wider range of operations than binary transistors.

Like a cerebral synapse, a memristor would also be able to “remember” the value associated with a given current force and produce exactly the same signal the next time it receives a similar current. This could ensure that the response to a complex equation or the visual classification of an object is reliable – an achievement that typically involves several transistors and capacitors.

Finally, scientists predict that memristors would require much less chip space than conventional transistors, allowing for powerful, portable computing devices that don’t rely on supercomputers or even Internet connections.

Existing memristor designs, however, are limited in performance. A single memristor is composed of a positive and negative electrode, separated by a “switching means” or space between the electrodes. When a voltage is applied to one electrode, the ions of that electrode flow through the medium, forming a “conduction channel” for the other electrode. The ions received make up the electrical signal that the memristor transmits through the circuit.

The size of the ion channel (and the signal that the memristor finally produces) must be proportional to the strength of the stimulating voltage. Kim says that existing memristor designs work very well in cases where the voltage stimulates a large conduction channel or an intense flow of ions from one electrode to another.

But these designs are less reliable when mem ristors need to generate more subtle signals, through thinner conduction channels. The thinner the conduction channel, and the less the flow of ions from one electrode to the other, the more difficult it is for the individual ions to stay together. Instead, they tend to move away from the group, dispersing in the middle.

As a result, it is difficult for the receiving electrode to safely capture the same number of ions and therefore transmit the same signal when stimulated with a certain low range of ions chain.

Metallurgy loans

Kim and his colleagues found a way around this limitation by borrowing a technique from metallurgy, the science of melting metals into alloys and studying their combined properties.

“Traditionally, metallurgists have tried to add different atoms in a bulk matrix to strengthen materials,and we thought: why not adjust the atomic interactions in our memristor and add some alloying element to control the movement of ions in our environment,” says Kim .

Engineers typically use silver as the material for a memristor’s positive electrode. Kim’s team examined the literature to find an element that they could combine with silver to effectively hold the silver ions together, allowing them to floqquickly through the other electrode.

The team identified copper as the ideal alloying element, as it is capable of binding both silver and silicon.

“It acts as a kind of bridge and stabilizes the silver-silicon interface,” says Kim. To create memristors using their new alloy, the group first manufactured a negative electrode from silicon and then produced a positive electrode by depositing a small amount of copper, followed by a layer of silver. They placed the two electrodes around an amorphous silicon medium.

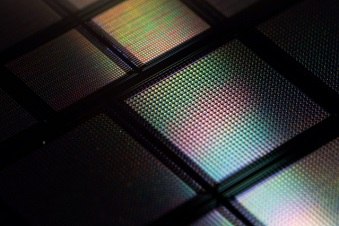

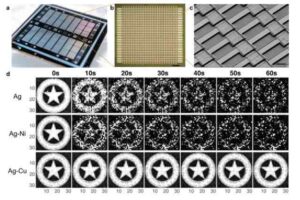

In this way, they modeled a square millimeter silicon chip with tens of thousands of memristors.

As a first test of the chip, they recreated a grayscale image of Captain America’s shield. They matched each pixel in the image to a corresponding memristor on the chip. They then modulated the conductance of each memristor that had color relative strength at the corresponding pixel. The chip produced the same sharp image as the shield and was able to “remember” the image and reproduce it many times, compared to chips made of other materials.

The team also ran the chip in an image processing task, programming memristors to alter an image, in the case of MIT’s Killian Court, in several specific ways, including sharpening and blurring the original image. Again, its design produced the reprogrammed images more reliably than the memristors‘ existing designs.

“We are using artificial synapses to do real inference tests,” says Kim. “We would like to further develop this technology to have larger-scale arrays to perform image recognition tasks. And someday, you’ll be able to transport artificial brains to perform this kind of task, without connecting to supercomputers, the Internet or the cloud. “

This research was supported, in part, by funds from the MIT Research Support Committee, the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab, the Samsung Global Research Laboratory and the National Science Foundation.

Related article: MIT – Mix and match materials for new advanced wearable flexible electronics