Views: 17

– “To combat academic dishonesty, focus on educational systems, not just individual aggressors,” says Tracey Bretag.

Courtesy Nature by Tracey Bretag: Stories of students who pay others to do their work come from all over the world. In the 2015 MyMaster scandal in Australia, hundreds of students enrolled in more than a dozen universities paid a total of at least $ 160,000 ($ 108,000) to a ‘service’ that provided ghost-written essays and answers to online tests. line. In 2018, YouTube stars on more than 250 channels received money to promote a cheating service called EduBirdie. Similar companies were discovered in the United States and elsewhere. Scientists should not be fooled: they are not immune. Academics call this “contract fraud.”

My colleagues and I have gathered what is, as far as we know, the largest data set on the subject – with responses from about 14,000 students and 1,000 professors at 8 Australian universities. We found that approximately 6% of students were involved in the practice; whereas most fraudsters do so more than once; and that graduate and graduate students get involved in it. Fraud is not new, but the proliferation of commercial online services over the past 5 to 10 years has made it easier than ever.

Fraud is becoming increasingly normal. Since the 1990s, universities around the world have re-imagined themselves as commercial companies promoting educational ‘products’ for student ‘consumers’. In 2017, a commentator compared the brash marketing strategies of some UK universities to shampoo advertising, and hundreds of scholarly works openly criticized the ‘commercialization’ of higher education. No wonder students choose to take the most convenient path to obtaining an academic credential – just as they would buy any other agreement. In our survey, more than a third of teachers specifically blamed contract fraud in the marketing of higher education.

Student survey data uncovered three factors associated with contract fraud: speaking English as a second language; thinking that there are many opportunities for fraud; and dissatisfaction with the educational environment. Two trends – diminishing teaching resources and lower language and academic admission standards – contribute to the situation. And while little research has been done on the frequency of this phenomenon in scientific researchers, those who are forced to outsource their written work as undergraduate students are likely to be tempted to do so as under pressure to “publish or perish.”

A cursory Google search for ‘ghost services for researchers’ identifies thousands of services that offer complete dissertations, grant applications, conference papers, and journal articles. Clothing selling research papers has been discovered in China and Iran, and the ghost doctoral dissertation market is booming in Ukraine and looks healthy in Australia.

We need to recognize that contract fraud is not just the responsibility of students, teachers or institutions. It is a systemic issue. Government funding agencies, regulators, and higher education leaders must face it.

Initiatives to combat contract fraud

Some made a good start. In 2018, New Zealand successfully sued the Assignments4U trade fraud service, which paid NZ $ 2.1 million ($ 1.3 million) in an out-of-court settlement and closed. In April 2019, the Australian Department of Education introduced a bill aimed at commercial services that advertise or provide unauthorized student assistance. It is expected to become law next year. Ireland has a similar law in its books. Such laws send a clear message. Fraud is not only unethical, it is illegal – and has consequences. Laws hold stakeholders critical to contract fraud over which educational institutions have no control.

“I feel that another important strategy is to reduce demand from within. Our team has found little concern for academics, including fraudulent, non-fraudulent students, and senior decision makers. They think fraudsters are just getting hurt and not hurting the community. ”

A radical change in rhetoric would help people see the value of actually doing their job. Institutions need to stop treating education as a product and refrain from determining the value of research by the amount of funding received or the number of articles produced. Instead, they should focus on building academic cultures that are committed to integrity and that place faith in the value of knowledge creation.

We cannot simply say to the people not to cheat. We must provide support for students to feel able to complete their assignments. This includes ensuring that institutions have appropriate language requirements for admission and allocating appropriate resources for teaching and learning.

Contract fraud is also a threat to public safety. It is not difficult to imagine how doctors, engineers and social workers who outsourced their learning could pose a risk. This practice even threatens the common understanding of scientific facts – a major concern in the age of ‘false news’. A large number of researchers who buy their theses, publications and qualifications would endanger the credibility of science.

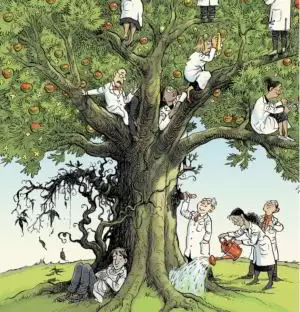

To defend itself, the scientific community must recognize that contract fraud is not an isolated problem caused by ‘bad apples’. It is an attack on core academic values that requires stronger leadership from government departments, funders, regulators, and educational institutions. This threat requires a collective response.

Related article: International AI ethics panel must be independent