Views: 84

by Bjarne Røsjø

Several types of antibiotics kill bacteria, for example, by destroying your cell wall or by interfering with protein synthesis. But now researchers at the University of Oslo (UiO) are launching a whole new idea: they want to prevent bacteria from sticking to a substrate, so can not cause infection or other injury.

Courtesy OiU: Researchers Dirk Linke, Marcella Rydmark and Daniel Hatlem of the Department of Biosciences are proposing a new method to break down intestinal infection bacteria Yersinia enterocolitica, which causes severe diarrhea in about 10 million children each year – especially in the poorest countries of the world.

But the new method should also be used to fight harmful bacteria and biofilms, such as communities of bacteria attached to a surface – for example, in prostheses and implants. At the same time, the method may give the pharmaceutical industry a new weapon in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which is a major and growing problem in rich and poor countries.

In addition, researchers visualize a number of possible applications, for example in the shipping industry and the aquaculture industry, where bacteria and biofilms can be a major problem.

“It’s all about attacking bacteria in a whole new way,” the researchers say.

Let’s remove the “Velcro” from the bacteria

– If the bacteria cause an infection, they must first be able to bind to a cell. The same applies when bacteria form biofilms; then they must join a surface. During evolution, bacteria have developed a number of “techniques” that make it possible, says Professor Dirk Linke.

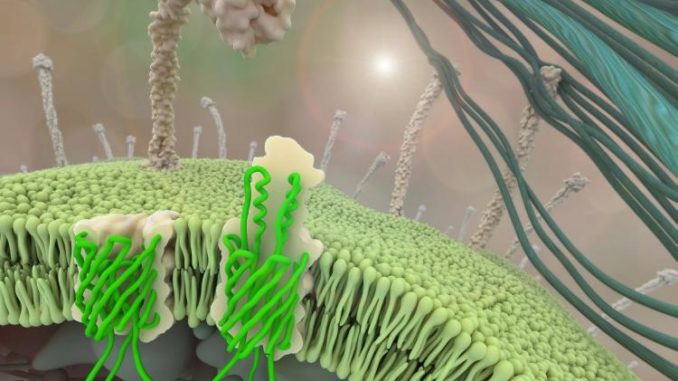

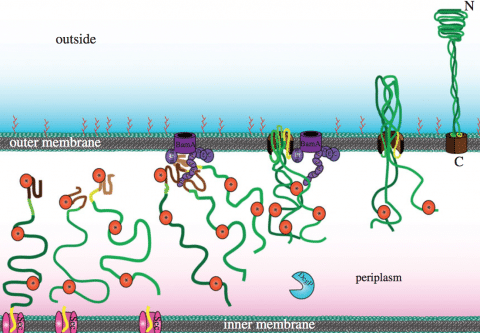

One of the main tricks that bacteria use when attaching to a cell or other surface is to produce some very sticky molecules – the adhesins – that cover the surface of the bacterial cell. Thus, a bacterium may use the adhesins to bind to a substrate, or to make a biofilm by binding to other bacteria. By interfering with the production of the adhesins, we can potentially combat infections already in the initial phase – that is, before the symptoms occur, adds Marcella Rydmark.

The adhesins actually consist of a kind of long strand or hair-like proteins with a sticky tip. The hairs can grow with such force that they cover more or less the bacterial surface, as if the bacteria were covered by velcro.

Dirk Linke, Marcella Rydmark and Daniel Hatlem are now the first to describe how these Velcro-type hair – that is, adhesins – are produced inside the bacterial cells and transported to the surface. They also studied how you can block this process. The new findings were presented in a recent scientific paper published in Molecular Microbiology.

– A blockage of adhesins in practice will cause bacteria to lose their ability to bind to anything. So they can not biofilm or cause infections, researchers believe.

Long-term work

It is a long-term job over more than ten years behind the new discovery. About two years ago, researchers from the Dirk Linke group reported that they discovered the adhesin of the Yersiniausa bacteria that binds to human cells when they cause serious illness. And now they have figured out how they can block the production of this adhesin.

There is reason to believe that adhesin-like surface proteins not only cause diarrhea but also play a role in the development of other diseases, such as tuberculosis, plague and cystic fibrosis.

Artificial hips and other surgical implants are sometimes covered by biofilm, which can cause infections so severe that the implants should be removed again. It is also relatively common for people with urinary tract infections to develop biofilm-like structures within the cells along the urinary tract, and this can act as a reservoir for new infections.

“So we believe this is a breakthrough when we now show how we can block the production of a velcro protein in a bacterium. But I want to emphasize that it will still take time before we can introduce a new drug. We can talk about five or ten years of continuous research and development, says Linke.

Ten million children are infected annually from diarrhea

Dirk Linke and his research group initially focused on a molecule of adhesin Yersinia enterocolitica, which is an important cause of diarrhea in poor countries. There are about ten million children infected each year by this bacteria, says Linke – who now hopes that new knowledge of the “Velcro” of the bacteria in the future can remedy these problems.

– The bacteria Yersinia can not cause diarrhea if it does not produce biofilm and adhere to the interior of the intestine; then it is just washed out of the body. If we are able to prevent the production of “velcro closures” of this bacterium, we will have mastered the crack of the disease, says Rydmark.

– In our rich part of the world, many people die of cancer or cardiovascular diseases, but in poor countries many of the other bacterial diseases die. Unfortunately, pharmaceutical companies will not invest large sums in drug development because they have a large market in poor countries and may not earn enough to defend investments, says Linke – adding:

– It is therefore particularly important that universities and public authorities take responsibility in this area! Pharmaceutical companies also will not fund projects if they have to wait five or ten years before they have a product that can make a profit, and we can understand that. But we firmly believe that we are on the path to something that can save many human lives, and we therefore hope to continue the public funding of this research, says Linke.

Mutation prevents the formation of adhesin

The researchers describe in the scientific paper how they studied the genes that give rise to the production of adhesin proteins within the cells of Yersinia enterocolitica. They also studied which parts of the protein are central during transport from the interior of the bacterium to the cell membrane. In addition, the researchers introduced mutations that block this process.

– We have come a long way to understand which part of the adhesin protein can be blocked by mutations. The next step is to develop a molecule that binds to that part of the protein, and this can become a drug in the future. This makes the project a very classic development process, which we have good opportunities to do here at the UIO and the Norwegian Center for Molecular Medicine (NCMM), “says Linke.

Marcella Rydmark emphasizes that bacteria do not die if they are exposed to a drug that only destroys adhesin production. It may actually be an advantage because bacteria are less likely to develop new defense mechanisms through evolution. A bacterium unable to produce adhesin may still be able to reproduce itself.

– No drug that attacks these adhesin molecules has been developed previously. This means that bacteria can not use any of the “old” techniques they have developed to protect themselves against antibiotics, she adds. However, if there is still a point to completely remove the bacteria, the new drug can be used in combination with other drugs.

Biofilms are everywhere

The UIO researchers have already received many comments from other interested researchers. Over the next few months, they will, among other things, present the new findings at various scientific conferences.

Biofilms are more widespread than most people think. Both a soft velvety plaque and a thick plaque on the tooth that a dentist needs to remove are examples of biofilms.

There are also biofilms in almost every place in nature, where you have a solid surface and an aqueous environment. You may have noticed that the stones in running water can be very slippery – and this may be because they are covered by a biofilm that contains several different bacteria. But it does not just have that biofilm and will not let go. Linke, Rydmark, Hatlem

Contact:

Professor Dirk Linke, Department of Biosciences

Postdoctoral researcher Marcella O. Rydmark, Department of Life Sciences

Daniel Hatlem, Department of Biosciences

Leave a Reply